Other Neurological Conditions

Supporting the unique abilities and talents of individuals to build brighter futures

Empowering Children Affected by Neurological Conditions. Our Trust is dedicated to providing compassionate support and vital resources to children navigating neurological challenges. From autism spectrum disorders to rare genetic conditions, we offer tailored assistance, therapies, and educational programs. Together, we strive to cultivate a nurturing environment where every child can thrive, regardless of their neurological differences. Join us in our mission to create a brighter future for these resilient young individuals, offering them the tools and opportunities they need to reach their full potential and live fulfilling lives.

Neurological Conditions

Movement Disorders

Movement disorders are neurologic conditions that cause problems with movement, such as:

Increased movement that can be voluntary (intentional) or involuntary (unintended)

Decreased or slow voluntary movement.

There are many different movement disorders. Some of the more common types include:

Ataxia, the loss of muscle coordination

Dystonia, in which involuntary contractions of your muscles cause twisting and repetitive movements. The movements can be painful.

Huntington's disease, an inherited disease that causes nerve cells in certain parts of the brain to waste away. This includes the nerve cells that help to control voluntary movement.

Parkinson's disease, which is disorder that slowly gets worse over time. It causes tremors, slowness of movement, and trouble walking.

Tourette syndrome, a condition which causes people to make sudden twitches, movements, or sounds (tics)

Tremor and essential tremor, which cause involuntary trembling or shaking movements. The movements may be in one or more parts of your body.

Causes of movement disorders include:

- Genetics

- Infections

- Medicines

- Damage to the brain, spinal cord, or peripheral nerves

- Metabolic disorders

- Stroke and vascular diseases

- Toxins

Treatment varies by disorder. Medicines can cure some disorders. Others get better when an underlying disease is treated. Often, however, there is no cure. In that case, the goal of treatment is to improve symptoms and relieve pain.

Muscular dystrophy

Muscular dystrophy is a group of diseases that cause progressive weakness and loss of muscle mass.

In muscular dystrophy, abnormal genes (mutations) interfere with the production of proteins needed to form healthy muscle.

There are many kinds of muscular dystrophy. Symptoms of the most common variety begin in childhood, mostly in boys. Other types don't surface until adulthood.

There's no cure for muscular dystrophy. But medications and therapy can help manage symptoms and slow the course of the disease.

Symptoms

The main sign of muscular dystrophy is progressive muscle weakness. Specific signs and symptoms begin at different ages and in different muscle groups, depending on the type of muscular dystrophy.

Duchenne type muscular dystrophy

This is the most common form. Although girls can be carriers and mildly affected, it's much more common in boys.

Signs and symptoms, which typically appear in early childhood, might include:

Frequent falls

Difficulty rising from a lying or sitting position

Trouble running and jumping

Waddling gait

Walking on the toes

Large calf muscles

Muscle pain and stiffness

Learning disabilities

Delayed growth

Becker muscular dystrophy

Signs and symptoms are similar to those of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, but tend to be milder and progress more slowly. Symptoms generally begin in the teens but might not occur until the mid-20s or later.

Other types of muscular dystrophy

Some types of muscular dystrophy are defined by a specific feature or by where in the body symptoms begin. Examples include:

Myotonic This is characterized by an inability to relax muscles following contractions. Facial and neck muscles are usually the first to be affected. People with this form typically have long, thin faces; drooping eyelids; and swanlike necks.

Facioscapulohumeral (FSHD). Muscle weakness typically begins in the face, hip and shoulders. The shoulder blades might stick out like wings when arms are raised. Onset usually occurs in the teenage years but can begin in childhood or as late as age 50.

Congenital This type affects boys and girls and is apparent at birth or before age 2. Some forms progress slowly and cause only mild disability, while others progress rapidly and cause severe impairment.

Limb-girdle Hip and shoulder muscles are usually affected first. People with this type of muscular dystrophy might have difficulty lifting the front part of the foot and so might trip frequently. Onset usually begins in childhood or the teenage years.

Neuropathy

Peripheral neuropathy happens when the nerves that are located outside of the brain and spinal cord (peripheral nerves) are damaged.

This condition often causes weakness, numbness and pain, usually in the hands and feet. It also can affect other areas and body functions including digestion and urination.

The peripheral nervous system sends information from the brain and spinal cord, also called the central nervous system, to the rest of the body through motor nerves. The peripheral nerves also send sensory information to the central nervous system through sensory nerves.

Peripheral neuropathy can result from traumatic injuries, infections, metabolic problems, inherited causes and exposure to toxins. One of the most common causes of neuropathy is diabetes.

People with peripheral neuropathy usually describe the pain as stabbing, burning or tingling. Sometimes symptoms get better, especially if caused by a condition that can be treated. Medicines can reduce the pain of peripheral neuropathy.

Symptoms

Every nerve in the peripheral system has a specific job. Symptoms depend on the type of nerves affected. Nerves are divided into:

Sensory nerves that receive sensation, such as temperature, pain, vibration or touch, from the skin.

Motor nerves that control muscle movement.

Autonomic nerves that control functions such as blood pressure, sweating, heart rate, digestion and bladder function.

Symptoms of peripheral neuropathy might include:

Gradual onset of numbness, prickling, or tingling in your feet or hands. These sensations can spread upward into your legs and arms.

Sharp, jabbing, throbbing or burning pain.

Extreme sensitivity to touch.

Pain during activities that shouldn't cause pain, such as pain in your feet when putting weight on them or when they're under a blanket.

Lack of coordination and falling.

Muscle weakness, Feeling as if you're wearing gloves or socks when you're not.

Inability to move if motor nerves are affected.

If autonomic nerves are affected, symptoms might include:

Heat intolerance.

Excessive sweating or not being able to sweat.

Bowel, bladder or digestive problems.

Drops in blood pressure, causing dizziness or lightheadedness.

Peripheral neuropathy can affect one nerve, called mononeuropathy. If it affects two or more nerves in different areas, it's called multiple mononeuropathy, and if it affects many nerves, it's called polyneuropathy. Carpal tunnel syndrome is an example of mononeuropathy. Most people with peripheral neuropathy have polyneuropathy.

Headaches

The exact cause of headaches is not completely understood. It is thought that many headaches are the result of tight muscles and dilated, or expanded, blood vessels in the head.

Although migraine headaches were previously thought to be due to dilated blood vessels in the brain, newer theories suggest that changes in brain chemicals or electrical signaling may be involved.

Other headaches may be caused by an alteration in the communication between parts of the nervous system that relay information about pain, coming from the area of the head, face, and neck. Lack of sleep and poor sleep quality are often the cause of chronic headaches. Occasionally, there is an actual problem in the brain, such as a tumor or malformation of the brain, although this is rare.

The way a child exhibits a headache may be related to many factors, such as genetics, hormones, stress, diet, medications, and dehydration. Recurrent headaches of any type can cause school problems, behavioral problems, and/or depression.

Primary headaches

These are usually caused by tight muscles, dilated blood vessels, alterations in communication between parts of the nervous system, or inflammation of the structures in the brain and are not linked to another medical condition. Types of primary headaches include the following:

Migraines

Migraines may start early in childhood. It is estimated that nearly 20 percent of teens experience migraine headache.

The average age of onset is 7 years of age for boys and 10 years of age for girls. There is often a family history of migraines.

Some females may have migraines that correlate with their menstrual periods. While every child may experience symptoms differently, the following are the most common symptoms of a migraine:

Pain on one or both sides of the head (some younger children may complain of pain all over)

Pain may be throbbing or pounding in quality (although young children may not be able to describe their pain)

Sensitivity to light or sound

Nausea and/or vomiting

Abdominal discomfort

Sweating

Child may become quiet or pale

Some children have an aura before the migraine, such as a sense of flashing lights, a change in vision, or funny smells

Tension headaches

Tension headaches are the most common type of headache. Stress and mental or emotional conflict are often factors in triggering pain related to tension headaches.

While every child may experience symptoms differently, the following are the most common symptoms of a tension headache:

Slow onset of the headache

Head usually hurts on both sides

Pain is dull or feels like a band around the head

Pain may involve the posterior (back) part of the head or neck

Pain is mild to moderate, but not severe

Change in the child's sleep habits

Children with tension headaches typically do not experience nausea, vomiting, or light sensitivity.

Cluster headaches

Cluster headaches usually start in children older than 10 years of age, and are more common in adolescent males. They are much less frequent than migraine or tension headaches.

Cluster headaches usually occur in a series that may last weeks or months, and this series of headaches may return every year or two, every child may experience symptoms differently.

Serious headache:

The child may have varying degrees of symptoms associated with the severity of the headache depending on the type of headache. Some headaches may be more serious.

Symptoms that may suggest a more serious underlying cause of the headache may include the following:

A very young child with a headache

A child that is awakened by the pain of a headache

Headaches that start very early in the morning

Pain that is worsened by strain, such as a cough or a sneeze

Recurrent episodes of vomiting without nausea or other signs of a stomach virus

Sudden onset of pain and the "worst headache" ever

Headache that is becoming more severe or continuous

Personality changes that have occurred as the headache syndrome evolved

Changes in vision

Weakness in the arms or legs, or balance problems

Seizures or epilepsy

How headaches are diagnosed

The full extent of the problem may not be completely understood immediately, but may be revealed with a comprehensive medical evaluation and diagnostic testing. The diagnosis of a headache is made with a careful history and physical examination and diagnostic tests. During the examination, the doctor obtains a complete medical history of the child and family.

Treatment for headaches

Specific treatment for headaches will be determined by your child's doctor based on:

Your child's age, overall health, and medical history

Extent of the headaches

Type of headaches

Your child's tolerance for specific medications, procedures, or therapies

Your opinion or preference

The ultimate goal of treatment is to stop the headache from occurring. Medical management relies on the proper identification of the type of headache and may include:

Rest in a quiet, dark environment, Medications, as recommended by your child's doctor & Stress management

Avoid known triggers, such as certain foods and beverages, lack of sleep, and fasting

Diet changes & Exercise

Migraine headaches may require specific medication management including:

Abortive medicines. Medicines, prescribed by your child's doctor, that act on specific receptors in blood vessels in the head and can stop a headache in progress.

Rescue medicines. Medicines purchased over-the-counter, such as analgesics (pain relievers), to stop the headache.

Preventive medicines. Medicines, prescribed by your child's doctor, that are taken daily to reduce the onset of severe migraine headaches.

Some headaches may require immediate medical attention including hospitalization for observation, diagnostic testing, or even surgery.

Treatment is individualized depending on the extent of the underlying condition that is causing the child's headache.

The extent of the child's recovery is individualized depending on the type of headache and other medical problems that may be present.

Concussions.

A concussion is a brain injury that affects the way the brain works and can lead to symptoms such as headache, dizziness, and confusion.

Symptoms usually go away within a few days to a month with rest and a gradual return to school and regular activities. Sometimes, the symptoms last longer.

Symptoms of a concussion might happen right after the head injury or develop over hours to days. They can include:

Headache, confusion, dizziness, vision changes, nausea and/or vomiting, trouble walking and talking, not remembering the injury, not remembering before or after the injury, feeling sluggish,

Someone with a concussion also might have focus or learning problems, sleep problems, anxiety, or sadness.

Concussions can follow being knocked out (losing consciousness) from a head injury, but they can happen without a person being knocked out.

What Happens in a Concussion

A concussion happens when the brain is injured. This can happen when the head is hit — for example, from a fall. But concussions also can happen without a blow to the head — for example, in a car accident when the head snaps forcefully forward and back. The strong movement causes chemical and blood flow changes in the brain. These changes lead to concussion symptoms.

How Do Kids and Teens Get Concussions

Most concussions in kids and teens happen while playing sports. The risk is highest for cheerleaders and kids who play football, ice hockey, lacrosse, soccer, and field hockey.

Kids also can get a concussion from a car or bike accident, fall, fight, or anything that leads to a head injury.

To diagnose a concussion, the expert at ICON Foundation may:

Ask about how and when the head injury happened, Ask about symptoms, Test memory and concentration, Do an exam and test balance, coordination, and reflexes

Concussions do not show up on a CAT scan or MRI. Those tests might be done to look for other problems if someone:

Was knocked out, keeps vomiting, has a severe headache or a headache that gets worse, was injured in a serious accident, such as from a car crash or very high fall

How Are Concussions Treated?

Healing from a mild concussion involves a gradual return to activities that finds a balance between doing too much and too little.

For the first day or two, your child should cut back on physical activities and those that take a lot of concentration (such as schoolwork). Have them relax at home. They can sleep if they feel tired. Calm activities such as talking to family and friends, reading, drawing, coloring, or playing a quiet game are OK. They should avoid all screen time (including TVs, computers, and smartphones) for the first 2 days after the concussion.

Usually within a day or so, they can start adding more activities, such as going for a walk. They should continue to avoid sports and any activity that could lead to another concussion. Symptoms don't have to be completely gone for your child to add activities. But if symptoms get worse with an activity, they need to take a break from it. They can try it again later that day or the next day, or try a less intense version of it.

Keep your child out of all sports and any activities that could lead to head injury (like rough play, or riding a bike or skateboard) until their symptoms are completely gone and they're cleared by a health care provider. It’s important to prevent another concussion because repeated concussions can have long-lasting, serious effects on the brain.

After a few days, your child should feel well enough to return to school. Work with your health care provider and a school team to create a plan for returning to school. Your child may need to start with a shorter day or a lighter workload.

Don't let your teen drive until your health care provider says it’s OK.

Other things that can help:

When your child goes back to doing screen time, help them limit how much time they spend on it. Video games, texting, watching TV, and using social media are likely to cause symptoms or make them worse.

Make sure your child gets plenty of sleep. They should: Keep regular sleep and wake times. Avoid screen time or listening to loud music before bed. Avoid caffeine.

For the first few days after the injury, if your child has a headache, they can take acetaminophen (Tylenol or a store brand) or ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, or a store brand). Follow the directions on the label for how much to give and how often.

Someone healing from a concussion should: Ease back into activities as symptoms get better. Get plenty of sleep. Not go back to sports until cleared by their health care provider.

Visit the doctor at ICON Foundation immediately if your child:

Is not back in school by 5 days after the concussion

Isn't doing their usual level of schoolwork after being back to school for 2 weeks

Still needs medicine for headache a week or more after the injury

Has symptoms (such as headache, vomiting, confusion, or dizziness) that aren’t getting better or get worse

Still has symptoms 4 weeks after the concussion

Passes out

What else to know

Your child needs your support as they heal from the concussion. Help them add reasonable activities but also recognize when the body and brain need more time to heal. Never tell your child to “tough it out” if they have trouble with an activity. This can slow their recovery and may make the concussion symptoms worse. Don’t let your child go back to sports before they're cleared to do so by a health care provider. Getting another head injury before the concussion is healed can be very dangerous.

The symptoms can be different with each concussion. Repeated concussions may even lead to permanent brain changes. Not all concussions can be prevented, but you can take steps to make another one less likely. If your child does get another head injury, they need to stop the sport or activity and tell you, a coach, teacher, or trusted adult right away. Then call your health care provider, who might want to see your child.

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is a neurological condition characterized by an episode (attack) of inflammation in your central nervous system.

The attack often damages the protective covering around your nerve axon, called the myelin sheath, which helps transmit information between nerve cells.

Like the plastic cover around electrical wires, myelin surrounds your nerve fibers to help electrical signals move to other nerve cells in your body. If you have damage to your myelin, you may experience symptoms like vision loss and muscle weakness.

A healthcare provider may call ADEM a “demyelinating” condition. This condition is acute, meaning sudden. ADEM usually only occurs once but can sometimes happen again.

Symptoms of ADEM usually follow a viral or bacterial infection. The symptoms vary based on where the inflammation occurs and could include:

Fever, Headache, Nausea or vomiting, Confusion, Fatigue.

What causes ADEM

The exact cause of ADEM is unknown. Research suggests that an infection could trigger your immune system to respond to the threat abnormally, which causes symptoms of ADEM.

When a viral or bacterial infection enters your body, your immune system works to get rid of the infection that makes you sick. If you have ADEM, your immune system can mistake certain parts of your central nervous system for the bacteria or virus and attack it. This results in inflammation (swelling), which then causes the symptoms of ADEM.

Approximately 70% to 80% of people diagnosed with ADEM experience an infection or illness before they experience symptoms of ADEM. Most cases of ADEM begin about seven to 14 days after the infection.

What are the risk factors for ADEM?

Anyone can develop ADEM. It’s more common among children than adults. You’re more likely to get ADEM if you recently had an infection.

What are the complications of ADEM?

Complications of ADEM may include:

Memory loss, Cognitive processing delays, Coma. In very rare cases, symptoms of ADEM can be fatal.

Ongoing symptoms after treatment may include:

Severe headaches, Numbness, Trouble with coordination, Blurry vision.

How is ADEM diagnosed?

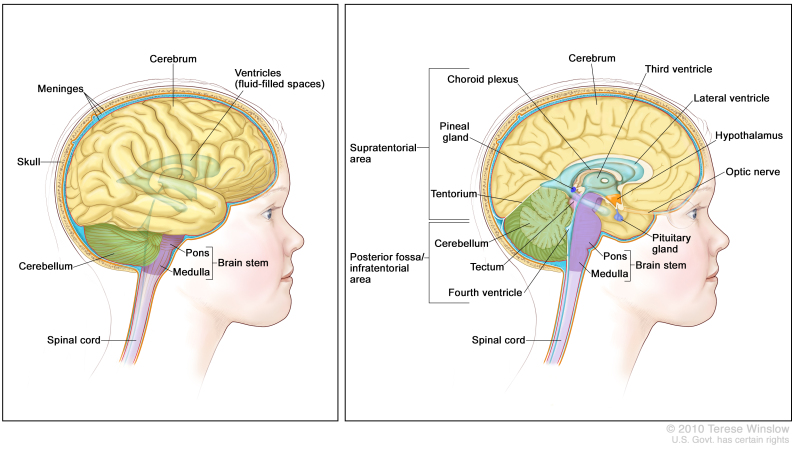

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a type of imaging test. It looks for changes deep within your brain. There are three areas in your central nervous system (brain, spinal cord, optic nerves) where a healthcare provider will look for changes, like lesions or spots, caused by ADEM:

White matter: The white matter contains nerve fibers. Myelin covers your nerve fibers and appears white on the basic MRI sequences.

Grey matter: The grey matter contains nerve cell bodies and no myelin. This gives it a darker appearance on basic MRI sequences.

Months after your first MRI, your healthcare provider may order another MRI to monitor how these areas of your central nervous system change over time.

Spinal fluid testing

A spinal tap or lumbar puncture is a diagnostic test that evaluates the cause of neurological symptoms. The lumbar puncture allows your neurological team to test your cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CSF is a clear, colorless fluid that circulates around your brain and spinal cord, protecting it and providing it with nutrients.

In ADEM, your spinal fluid often shows an increase in white blood cells, predominantly lymphocytes. These cells are an active part of your immune system. A healthcare provider may remove a sample of CSF to test your cells’ reaction to certain bacteria or viruses thought to trigger ADEM. It can also check for other neuroinflammatory diseases.

How is ADEM treated?

Treatment for ADEM focuses on reducing inflammation in your brain and spinal cord. Treatment may include:

Steroid medications: The first line of treatment for ADEM is usually intravenous (infusion through a vein) steroids. You may need more than one infusion followed by oral steroids (medications you take by mouth) to complete your treatment.

Intravenous immune globulin (IVIG): This is an antibody treatment that comes from donor plasma, given via infusion into a vein.

Plasma exchange: Plasma exchange or plasmapheresis circulates your blood through a machine that removes certain components to reduce your immune system’s activity. This treatment cycles blood from a vein into your arm into a machine and then back into a vein on your opposite arm. It can take a few hours to complete this treatment and you may need more than one session.

Research is ongoing to learn more about this condition and find new treatment options that can help you feel better.

Autoimmune encephalitis

Autoimmune encephalitis is a collection of related conditions in which the body’s immune system attacks the brain, causing inflammation.

The immune system produces substances called antibodies that mistakenly attack brain cells.

Like multiple sclerosis, the disease can be progressive (worsening over time) or relapsing-remitting (with alternating flare-ups and periods of recovery). Autoimmune encephalitis has many subtypes that depends on the antibodies present.

Left untreated, autoimmune encephalitis can quickly become serious. It may lead to coma or permanent brain injury. In rare cases, it can be fatal.

Autoimmune encephalitis was once considered rare, but doctors are finding more cases as their ability to diagnose it improves. A 2018 study found 13.7 cases per 100,000 people.

Factors that affect risk include:

Gender: This illness, like many autoimmune diseases, affects women more often than men.

Age: It can happen at any age but is diagnosed most often in young women.

Family history: It does not appear to run in families.

Race/ethnicity: It may be much more common among Black people, according to the 2018 study, but more research is needed.

In many cases, the cause of autoimmune encephalitis is unknown.

But experts say it can be caused by:

Exposure to certain bacteria and viruses, including streptococcus and herpes simplex virus.

A type of tumor called a teratoma, generally in the ovaries, that causes the immune system to produce specific antibodies.

Rarely, some cancers that can trigger an autoimmune response (when the immune system attacks the body’s own tissues).

Types of autoimmune encephalitis

Types include:

- Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)

- Anti-NMDAR receptor encephalitis

- Hashimoto’s encephalopathy

- LG11/CASPR2-antibody encephalitis

- Limbic encephalitis

- Rasmussen’s encephalitis

Symptoms may come on over a period of days or weeks. They can also vary depending on the type of autoimmune encephalitis.

The early phase of the disease may include flu-like symptoms, such as headache, fever, nausea and muscle pain. Psychiatric symptoms may appear, disappear and reappear. Later symptoms may be more severe, such as a lower level of consciousness and possible coma.

Common symptoms include:

- Impaired memory and understanding

- Unusual and involuntary movements

- Involuntary movements of the face (facial dyskinesia)

- Difficulty with balance, speech or vision

- Insomnia, Weakness or numbness

- Seizures, Severe anxiety or panic attacks

- Compulsive behaviors

- Altered sexual behaviors

- Behavior changes such as agitation, fear or euphoria

- Loss of inhibition, Hallucinations & Paranoid thoughts

- Loss of consciousness or coma

If you show signs of autoimmune encephalitis, your doctor will do a neurologic exam to measure your reflexes, nerve functions, thinking and other processes. You also may have tests to rule out other conditions.

Tests may include:

A spinal tap (lumbar puncture) to withdraw a sample of cerebrospinal fluid, the liquid that surrounds your brain and spinal cord. The fluid can be examined for signs of autoimmune encephalitis or another disease. Blood tests to look for antibodies that may indicate autoimmune encephalitis. MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans of your brain to identify signs of the disease.

Generally, a diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis requires three conditions:

Short-term memory loss, psychiatric symptoms or other symptoms of an altered mental state all within three months of one another

At least one of the following: Numbness, weakness or paralysis that affects a specific limb or area of the body

Seizures that can’t be explained by other conditions

A high white blood cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid

An MRI that shows signs of brain inflammation

Ruling out other causes

Treatment for autoimmune encephalitis

- Surgery to remove a teratoma.

- Steroids to reduce brain inflammation and the immune system’s response.

- Plasma exchange (removal and replacement of the liquid part of the blood) to take out harmful antibodies.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), given in an IV drip, to introduce antibodies from the plasma of healthy donors. IVIG removes harmful antibodies and reduces inflammation.

- Immunosuppressant medications, if other treatments are not effective.

Brain vessel malformations (with new, severe complications)

A brain arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is a tangle of blood vessels that connects arteries and veins in the brain.

The arteries take oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the brain. Veins carry the oxygen-depleted blood back to the lungs and heart. A brain AVM disrupts this vital process.

An arteriovenous malformation can develop anywhere in the body but common locations include the brain and spinal cord — though overall, brain AVMs are rare.

The cause of brain AVMs isn't clear. Most people are born with them, but they can form later in life. Rarely, they can be passed down among families.

Some people with a brain AVM experience signs and symptoms, such as headaches or seizures. An AVM is often found after a brain scan for another health issue or after the blood vessels rupture and bleed (hemorrhage).

Once diagnosed, a brain AVM can be treated to prevent complications, such as brain damage or stroke.

Symptoms

A brain arteriovenous malformation may not cause any signs or symptoms until the AVM ruptures, resulting in hemorrhage. In about half of all brain AVMs, hemorrhage is the first sign.

But some people with brain AVM may experience signs and symptoms other than bleeding, such as:

- Seizures

- Headache or pain in one area of the head

- Muscle weakness or numbness in one part of the body

- Some people may experience more-serious neurological signs and symptoms, depending on the location of the AVM, including:

- Severe headache

- Weakness, numbness or paralysis

- Vision loss

- Difficulty speaking

- Confusion or inability to understand others

- Severe unsteadiness

One severe type of brain AVM involves the vein of Galen. It causes signs and symptoms that emerge soon or immediately after birth. The major blood vessel involved in this type of brain AVM can cause fluid to build up in the brain and the head to swell. It can also cause swollen veins that are visible on the scalp, seizures, failure to thrive and congestive heart failure.

The cause of brain AVM is unknown. Researchers believe most brain AVMs are present at birth and form during fetal development, but brain AVMs can develop later in life, as well. Brain AVMs are seen in some people who have hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome. HHT affects the way blood vessels form in several areas of the body, including the brain.

Typically, the heart sends oxygen-rich blood to the brain through arteries. The arteries slow blood flow by passing it through a series of progressively smaller networks of blood vessels, ending with the smallest blood vessels (capillaries). The capillaries slowly deliver oxygen through their thin, porous walls to the surrounding brain tissue.

The oxygen-depleted blood passes into small blood vessels and then into larger veins that return the blood to the heart and lungs to get more oxygen.

The arteries and veins in an AVM lack this supporting network of smaller blood vessels and capillaries. Instead, blood flows quickly and directly from the arteries to the veins, bypassing the surrounding tissues.

Risk factors

Anyone can be born with a brain AVM, but these factors may raise the risk:

Being male. Brain AVMs are more common in males.

Having a family history. In rare cases, brain AVMs have been reported to occur in families, but it's unclear if there's a certain genetic factor or if the cases are only coincidental. It's also possible to inherit other medical conditions that increase the risk of brain AVMs, such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT). Complications of a brain AVM include:

Bleeding in the brain. An AVM puts extreme pressure on the walls of the affected arteries and veins, causing them to become thin or weak. This may result in the AVM rupturing and bleeding into the brain.

This risk of a brain AVM bleeding ranges from around 2% to 3% each year. The risk of bleeding may be higher for certain types of AVMs or if there's been a previous AVM rupture.

Some hemorrhages associated with AVMs go undetected because they cause no major brain damage or signs or symptoms. However, potentially life-threatening bleeding episodes may occur.

Brain AVMs account for about 2% of all hemorrhagic strokes each year. They're often the cause of hemorrhage in children and young adults who experience brain hemorrhage.

Reduced oxygen to brain tissue. With a brain AVM, blood bypasses the network of capillaries and flows directly from arteries to veins. Blood rushes quickly through the altered path because it isn't slowed by channels of smaller blood vessels.

Surrounding brain tissue can't easily absorb oxygen from the fast-flowing blood. Without enough oxygen, brain tissues weaken or may die off completely. This results in stroke-like symptoms, such as difficulty speaking, weakness, numbness, vision loss or severe unsteadiness.

Thin or weak blood vessels. An AVM puts extreme pressure on the thin and weak walls of the blood vessels. A bulge in a blood vessel wall (aneurysm) may develop and become susceptible to rupture. Brain damage. The body may recruit more arteries to supply blood to the fast-flowing brain AVM. As a result, some AVMs may get bigger and displace or compress portions of the brain. This may prevent protective fluids from flowing freely around the hemispheres of the brain.

If fluid builds up, it can push brain tissue up against the skull.

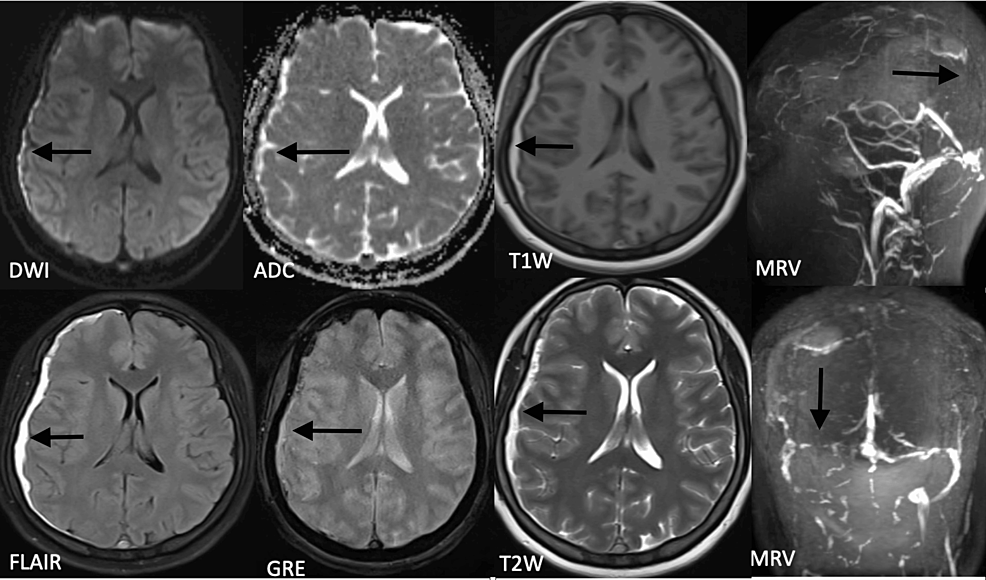

Cerebral sino-venous thrombosis (CSVT)

Cerebral Sinovenous Thrombosis (CSVT) occurs when a blood clot develops in a vein near the brain. Cerebral refers to the brain. Sinovenous refers to the large veins that drain the brain that are called venous sinuses.

With CSVT, the clot is in a vein that is carrying blood from the brain back to the heart. This type of clot is called a thrombus. Sometimes the blood clot goes away before it causes permanent brain damage. However, sometimes the clot remains and causes a type of stroke called a venous infarct, or may cause bleeding into the brain (brain hemorrhage).

The blood carries oxygen and other important nutrients to the brain. The brain needs oxygen to survive. When veins are blocked, the pressure in the veins "backs up" and makes it harder for blood to flow freely to brain tissue. If a part of the brain does not receive oxygen from the blood for a certain period of time, the tissue in that part of the brain will become damaged or die.

Causes

In most children, one or more causes or triggering conditions can be found. Leading causes of sinovenous thrombosis include:

- Dehydration-not having enough fluid in the body

- Ear or sinus infection that does not heal

- Heart disease

- Blood clotting disorders

- Serious infections

- Cancer and cancer treatments

- Immune system diseases including inflammatory bowel disease

- Head and neck surgery

- Accidents involving the head and neck region

- Birth control pills in teenage girls

- Signs and symptoms

Coma and other disorders of consciousness

Condition: Disorders of consciousness include coma (cannot be aroused, eye remain closed), vegetative state (can appear to be awake, but unable to purposefully interact) and minimally conscious state (minimal but definite awareness). Locked-in syndrome is not a disorder of consciousness but can look like one because of paralysis of limbs and facial muscles that causes an inability to speak and/or appearance of being unable to react.

Background: Most patients who survive injury to the brain regain consciousness but may have a disorder of consciousness. This may range from decreased awareness of surroundings to a persistent vegetative state. Patients with locked-in syndrome appear unable to react or speak, but the cause of this is paralysis of the limbs and facial muscles. Locked-in syndrome is often misdiagnosed as a disorder of consciousness.

Causes: Trauma, reduced blood supply or oxygen to the brain, and poisoning are leading causes for disorders of consciousness.

Disease Phases: Patients may be in a coma for several weeks after trauma. If patients survive, they may emerge into a vegetative state or minimally conscious state. The duration of vegetative state is variable which can be days to years and in some cases may be permanent. Emerging from a vegetative state resulting from trauma is more likely than from other causes, especially as time passes. There are some reports of people emerging from vegetative more than one year after traumatic brain injury, but not from other causes. Patients emerging from a minimally conscious state show signs of being able to interact and communicate.

Physical Exam: Healthcare providers perform neurological examinations at the bedside to assess if the patient’s responses to commands are reflexive or voluntary.

Diagnostic Process : There are no laboratory or imaging tests available to diagnose disorders of consciousness. Several diagnostic scales or profiles can assess the level of a patient’s brain injury and prognosis, and help healthcare providers develop a treatment plan. These assessments evaluate a patient’s attention, communication, response to stimulation, vision and ability to follow commands.

Rehabilitation Management: The Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R) Physician oversees medical management which focuses on improving consciousness as well as preventing and managing complications from prolonged immobility. They provide general health care that includes keeping skin healthy, stretching arms and legs, and bowel and bladder management. Patients may develop spasticity, pneumonia, or blood clots. Amantadine is a medication that may improve arousal if given during the weeks after traumatic brain injury. Other medications and physical means to stimulate patients are also often given.

Outcomes : Trauma-related disorders have better outcomes among patients with disorders of consciousness than non-trauma causes. Rehabilitation during the first 6 months after traumatic brain injury may increase the chances of improving outcomes in people who are minimally conscious. Patients recovering at earlier time periods generally have better outcomes than those recovering at later times. PM&R Physicians have expertise in predicting functional prognosis.

Family Education: Family education regarding a patient’s prognosis and long-term planning are essential parts of disorders of consciousness care.

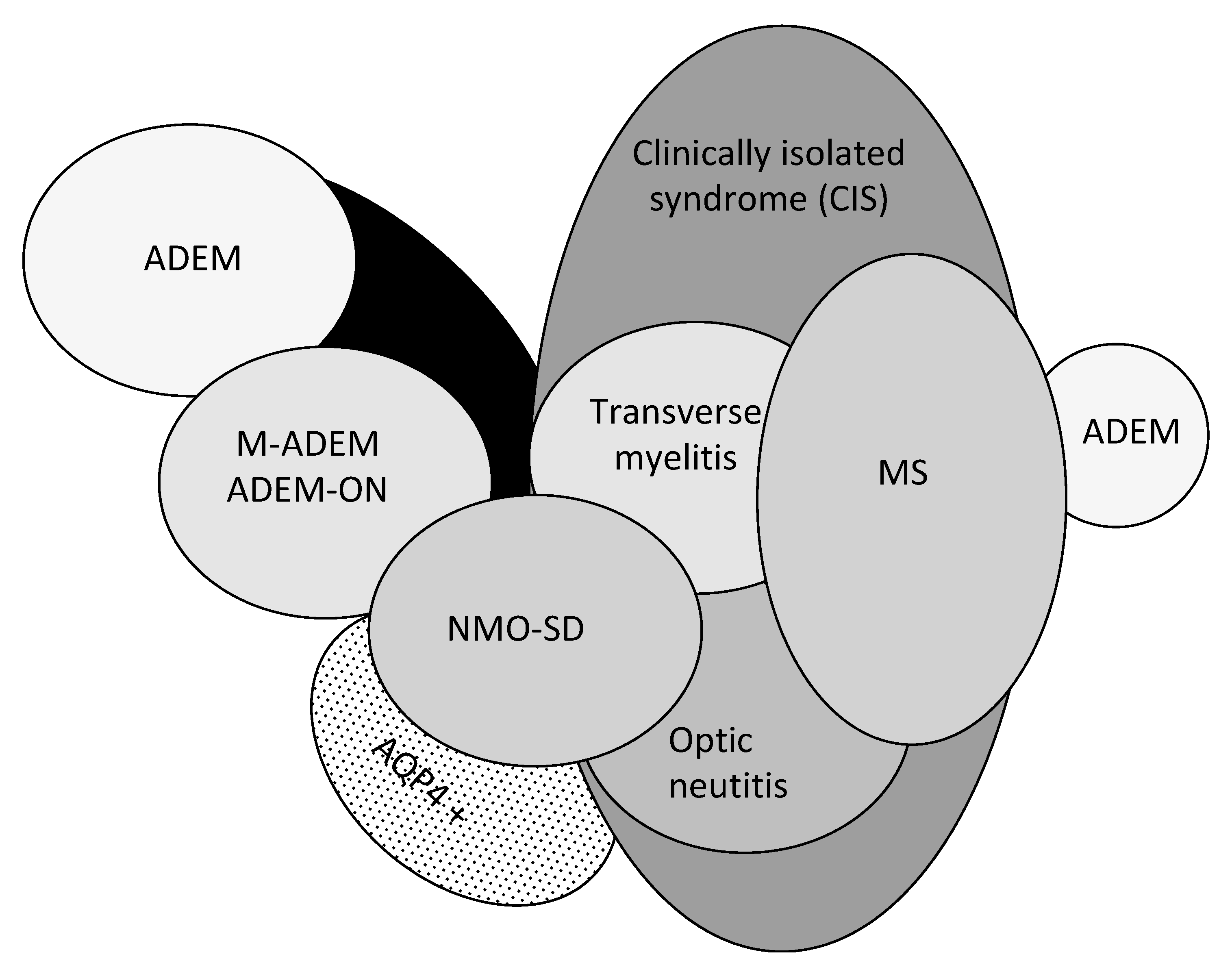

Demyelinating disease

In a demyelinating disease, the myelin sheath that protects the fibers in the central nervous system (brain, optic nerves and spinal cord) is damaged due to an attack on the immune system.

When this happens, it causes the nerve impulses to slow down, impacting the body’s function, or even stop, leading to symptoms that include paralysis and sensory loss.

- Conditions We Treat

- Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis (ADEM)

- Acute Flaccid Myelitis

- Anti-MOG Antibody Associated Disorder (anti-MOG)

- Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis

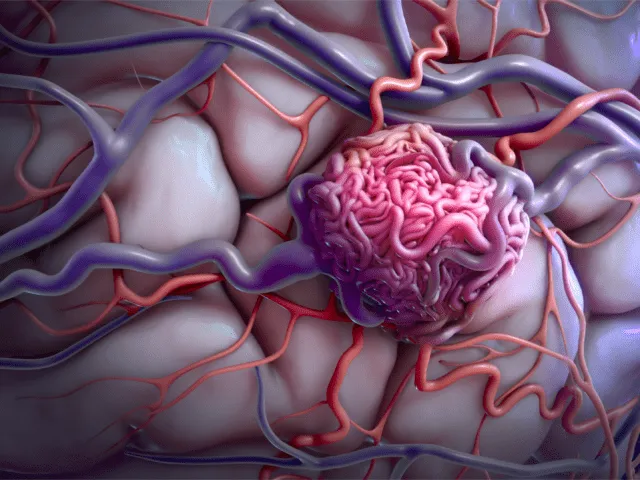

Emergency complications of malignancies of brain and spinal cord

Common emergencies arising that are the first signs of cancer in a previously well child and those occurring from treatment or at the time of tumor recurrence.

These emergencies are caused by space-occupying lesions, abnormalities of blood and blood vessels, or metabolic emergencies.

Some emergencies demand immediate attention; others are potentially life-threatening.

This distinction is as follows:

- Emergencies necessitating immediate intervention

- Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS)

- Spinal cord compression

- Brain herniation

- Hyperleukocytosis

- Emergencies with potential adverse consequences

- Massive hepatomegaly

- Leukopenia

- Coagulopathy

- Anemia

- Tumor lysis syndrome

- Hypercalcemia

Hepatic encephalopathy due to acute liver failure

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a reversible syndrome observed in patients with advanced liver dysfunction. This syndrome is characterized by a wide spectrum of neuropsychiatric abnormalities resulting from the accumulation of neurotoxic substances in the brain.

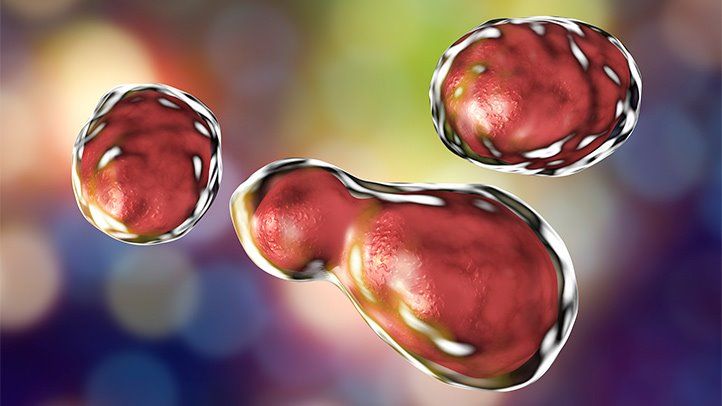

Infection of the spinal cord and brain

Infections of the brain can be caused by viruses, bacteria, fungi, or, occasionally, protozoa or parasites. Another group of brain disorders, called spongiform encephalopathies, are caused by abnormal proteins called prions.

Infections of the brain often also involve other parts of the central nervous system, including the spinal cord. The brain and spinal cord are usually protected from infection, but when they become infected, the consequences are often very serious.

Infections can cause inflammation of the brain (encephalitis). Viruses are the most common causes of encephalitis. Infections can also cause inflammation of the layers of tissue (meninges) that cover the brain and spinal cord—called meningitis. Often, bacterial meningitis spreads to the brain itself, causing encephalitis. Similarly, viral infections that cause encephalitis often also cause meningitis. Technically, when both the brain and the meninges are infected, the disorder is called meningoencephalitis. However, infection that affects mainly the meninges is usually called meningitis, and infection that affects mainly the brain is usually called encephalitis.

Usually in encephalitis and meningitis, infection is not confined to one area. It may occur throughout the brain or within meninges along the entire length of the spinal cord and over the entire brain.

But in some disorders, infection is confined to one area (localized) as a pocket of pus, called an empyema or an abscess, depending on where it is located:

Empyemas form in an existing space in the body, such as the space between the tissues that cover the brain (meninges) or the lungs.

Abscesses, which resemble boils, can form anywhere in the body, including within the brain.

Fungi (such as aspergilli), protozoa (such as Toxoplasma gondii), and parasites (such as Taenia solium, the pork tapeworm) may cause cysts to form in the brain. These localized brain infections consist of a cluster of organisms enclosed in a protective wall.

Sometimes a brain infection, a vaccine, cancer, or another disorder triggers a misguided immune reaction, causing the immune system to attack normal cells in the brain (an autoimmune reaction). As a result, the brain becomes inflamed. This disorder is called postinfectious encephalitis.

Bacteria and other infectious organisms can reach the brain and meninges in several ways:

- By being carried by the blood

- By entering the brain directly from the outside (for example, through a skull fracture or during surgery on the brain)

- By spreading from nearby infected structures, such as the sinuses or middle ear

Intracranial hemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage is hemorrhage or bleeding into brain tissue. In children hemorrhage usually occurs due to abnormalities of the blood vessels (such as arteriovenous malformations, arteriovenous fistula, cavernous malformation, aneurysms, and moyamoya) or blood clotting.

In adults the most common cause is high blood pressure; however, this is rarely the cause in children.

Symptoms

The symptoms of intracerebral hemorrhage can include sudden, severe headache, especially with vomiting or and sleepiness, weakness of one side of the body, slurred speech, new onset of seizure, or loss of consciousness after one of the above symptoms.

Diagnosis

Computed tomography (CT) will show the hemorrhage, and further testing may include a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Depending on the results of the CT and/or MRI, further imaging may be requested. An angiogram (also called arteriogram) is a special test in which a neuroradiologist injects dye into the blood vessels in the brain and obtains images of the blood vessels. This test may be done when the diagnosis is unclear or to help plan treatment of a problem with the blood vessels. Other testing may include blood tests for clotting abnormalities.

Treatment

Treatment will depend on the cause of the child’s hemorrhage but may include surgical and endovascular treatments for abnormalities of blood vessels (endovascular means that a catheter is passed through the groin up into the arteries in the brain) and correction of blood clotting abnormalities if they are present.

Mitochondrial disorders

Mitochondrial disease, or mitochondrial disorder, refers to a group of disorders that affect the mitochondria, which are tiny compartments that are present in almost every cell of the body. The mitochondria’s main function is to produce energy. More mitochondria are needed to make more energy, particularly in high-energy demand organs such as the heart, muscles, and brain. When the number or function of mitochondria in the cell are disrupted, less energy is produced and organ dysfunction results.

Depending on which cells within the body have disrupted mitochondria, different symptoms may occur. Mitochondrial disease can cause a vast array of health concerns, including fatigue, weakness, metabolic strokes, seizures, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, developmental or cognitive disabilities, diabetes mellitus, impairment of hearing, vision, growth, liver, gastrointestinal, or kidney function, and more. These symptoms can present at any age from infancy up until late adulthood.

Every 30 minutes, a child is born who will develop a mitochondrial disorder by age 10. Overall, approximately 1 in every 4,300 individuals in the United States has a mitochondrial disease. Given the various potential presentations that may occur, mitochondrial disease can be difficult to diagnosis and is often misdiagnosed.

There are various methods to examine if an individual has mitochondrial disease. These include genetic diagnostic testing, genetic or biochemical tests in affected tissues, such as muscle or liver, and other blood or urine based biochemical markers. However, our knowledge is still growing and we do not yet know all of the genes that could potentially cause mitochondrial disease.

Mitochondria are unique in that they have their own DNA called mitochondrial DNA, or mtDNA. Mutations in this mtDNA or mutations in nuclear DNA (DNA found in the nucleus of a cell) can cause mitochondrial disorder. Environmental toxins can also trigger mitochondrial disease.

Mitochondrial disorder symptoms include:

- Poor growth

- Loss of muscle coordination, muscle weakness

- Neurological problems, including seizures

- Autism spectrum disorder, represented by a variety of ASD characteristics

- Visual and/or hearing problems

- Developmental delays, learning disabilities

- Heart, liver or kidney disease

- Gastrointestinal disorders, such as severe constipation

- Diabetes

- Respiratory disorders

- Increased risk of infection

- Thyroid and/or adrenal dysfunction

- Dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system

- Neuropsychological changes or dementia characterized by confusion, disorientation and memory loss

- Treatment for mitochondrial disease

Neuromuscular emergencies, including Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS), infant botulism, and myasthenia gravis

Guillain-Barré syndrome and myasthenia gravis are two neuromuscular disorders that can present with rapid respiratory compromise and subsequent mortality. Fortunately, they both present with hallmarks of clinical diagnosis that the emergency physician can use for early recognition.

Stroke

Pediatric stroke is a rare condition affecting one in every 4,000 newborns and an additional 2,000 older children each year. Stroke is a type of blood vessel (cerebrovascular) disorder. Strokes can be categorized as ischemic (caused by insufficient blood flow) and hemorrhagic (caused by bleeding into the brain). When a blood vessel in the brain is injured, the brain tissue around it loses blood supply and suffers injury as well. Treatments and long-term outcome in children are different for each type.

As with adults, without prompt and appropriate treatment, stroke in children can be life threatening and requires immediate medical attention. Stroke is among the top 10 causes of death in children. Pediatric stroke can also cause neurologic disability, with a risk of permanent long-term cognitive and motor impairment.

Stroke in children typically begins suddenly. Symptoms may include (but are not limited to) the following:

- Weakness or numbness on one side of the body

- Slurred speech or difficulty with language

- Trouble balancing or walking

- vision problems, such as double vision or loss of vision

- Sudden lethargy or drowsiness

- Seizure (unusual rhythmic movement of one or both sides of the body)

Traumatic brain and spinal cord injury

A traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a disruption of the normal function of the brain that can be caused by a bump, blow or jolt to the head or a penetrating head injury. While everyone is at risk for a TBI, children and older adults are especially vulnerable. Spinal cord injuries (SCI) describe injuries to the spinal cord. Symptoms of SCI can include partial or complete loss of sensory function or motor control of the arms, legs or body. In severe cases, SCI can affect bladder and bowel control, breathing, heart rate and blood pressure.

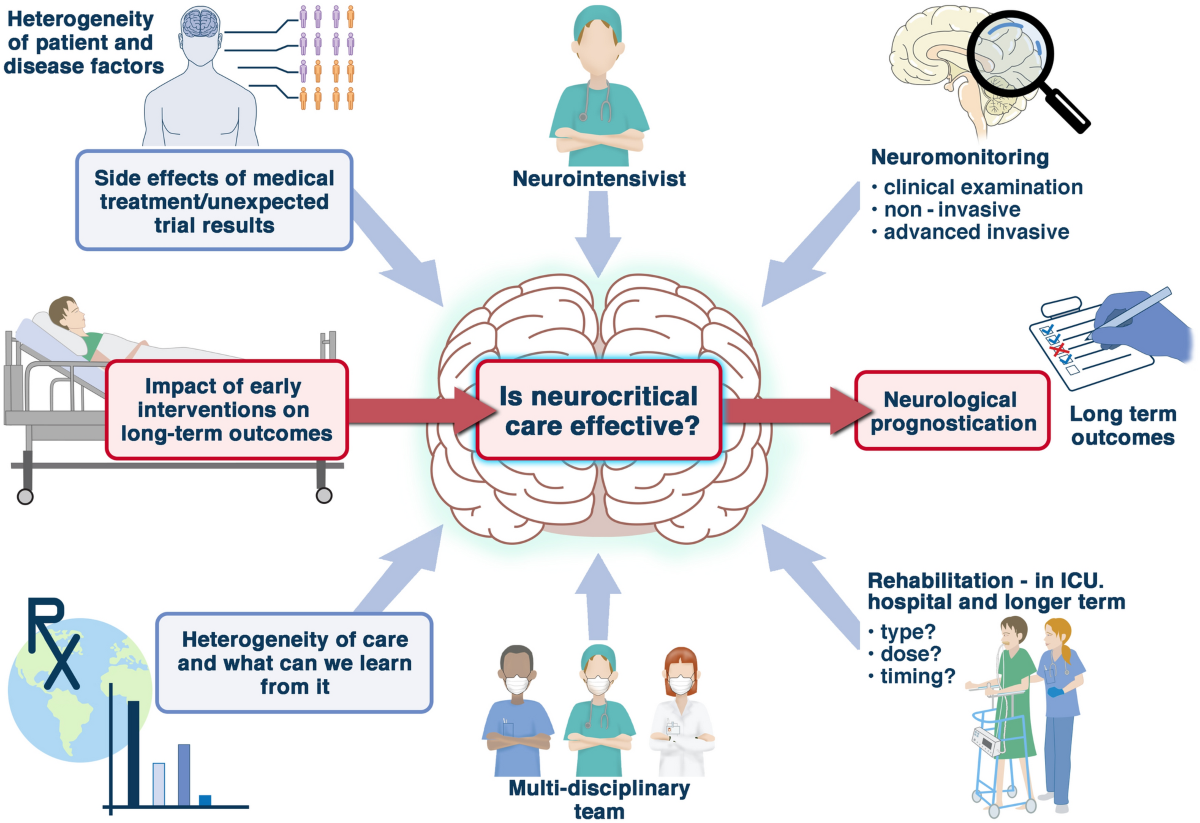

Neurologic complications of critical illness

All critical care is directed at maintaining brain health, but recognizing neurologic complications of critical illness in children is difficult, and limited data exist to guide practice.

Convulsive and nonconvulsive seizures occur frequently in children after cardiac arrest or traumatic brain injury and during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Seizures may add to neurologic morbidity, and continuous EEG monitoring is needed for up to 24 hours for detection. Hypothermia has not been shown to improve outcome after cardiac arrest in children, but targeted temperature management with controlled normothermia and prevention of fever is a mainstay of neuroprotection.

Much of brain-directed pediatric critical care is empiric. Recognition of neurologic complications of critical illness requires multidisciplinary care, serial neurologic examinations, and an appreciation for the multiple risk factors for neurologic injury present in most patients in the pediatric intensive care unit. Through attention to the fundamentals of neuroprotection, including maintaining or restoring cerebral perfusion matched to the metabolic needs of the brain, combined with anticipatory planning, these complications can be prevented or the neurologic injury mitigated.

Intellectual disability (also known as mental retardation)

Intellectual disability—formerly known as mental retardation—can be caused by injury, disease, or a problem in the brain. For many children, the cause of their intellectual disability is unknown.

Some causes of intellectual disability—such as Down syndrome, Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, birth defects, and infections—can happen before birth. Some happen while a baby is being born or soon after birth.

Other causes of intellectual disability do not occur until a child is older; these might include severe head injury, infections or stroke.

The most common causes of intellectual disabilities are:

Genetic conditions. Sometimes an intellectual disability is caused by abnormal genes inherited from parents, errors when genes combine, or other reasons. Examples of genetic conditions are Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, and phenylketonuria (PKU).

Complications during pregnancy. An intellectual disability can result when the baby does not develop inside the mother properly. For example, there may be a problem with the way the baby’s cells divide. A woman who drinks alcohol or gets an infection like rubella during pregnancy may also have a baby with an intellectual disability.

Problems during birth. If there are complications during labor and birth, such as a baby not getting enough oxygen, he or she may have an intellectual disability.

Diseases or toxic exposure. Diseases like whooping cough, the measles, or meningitis can cause intellectual disabilities. They can also be caused by extreme malnutrition, not getting appropriate medical care, or by being exposed to poisons like lead or mercury.

We know that intellectual disability is not contagious: you can’t catch an intellectual disability from anyone else. We also know it’s not a type of mental illness, like depression. There are no cures for intellectual disability. However, children with intellectual disabilities can learn to do many things. They may just need take more time or learn differently than other children.

Intellectual disability (ID) is characterized by below-average intelligence or mental ability and a lack of skills necessary for day-to-day living. People with intellectual disabilities can and do learn new skills, but they learn them more slowly. There are varying degrees of intellectual disability, from mild to profound.

Someone with intellectual disability has limitations in two areas. These areas are:

Intellectual functioning. Also known as IQ, this refers to a person’s ability to learn, reason, make decisions, and solve problems.

Adaptive behaviors. These are skills necessary for day-to-day life, such as being able to communicate effectively, interact with others, and take care of oneself.

IQ (intelligence quotient) is measured by an IQ test. The average IQ is 100, with the majority of people scoring between 85 and 115. A person is considered intellectually disabled if they have an IQ of less than 70 to 75.

To measure a child’s adaptive behaviors, a specialist will observe the child’s skills and compare them to other children of the same age. Things that may be observed include how well the child can feed or dress themselves; how well the child is able to communicate with and understand others; and how the child interacts with family, friends, and other children of the same age.

There are many different signs of intellectual disability in children. Signs may appear during infancy, or they may not be noticeable until a child reaches school age. It often depends on the severity of the disability. Some of the most common signs of intellectual disability are:

- Rolling over, sitting up, crawling, or walking late

- Talking late or having trouble talking

- Slow to master things like potty training, dressing, and feeding themselves

- Difficulty remembering things

- Inability to connect actions with consequences

- Behavior problems such as explosive tantrums

- Difficulty with problem-solving or logical thinking

Conduct disorders

Conduct disorder refers to a group of behavioral and emotional problems characterized by a disregard for others. Children with conduct disorder have a difficult time following rules and behaving in a socially acceptable way. Their behavior can be hostile and sometimes physically violent.

In their earlier years, they may show early signs of aggression, including pushing, hitting and biting others. Adolescents and teens with conduct disorder may move into more serious behaviors, including bullying, hurting animals, picking fights, theft, vandalism and arson.

Children with conduct disorder can be found across all races, cultures and socioeconomic groups. They often have other mental health issues as well that may contribute to the development of the conduct disorder. The disorder is more prevalent in boys than girls.

ICON Foundation offers a team of experts focused on the treatment of children with conduct disorders.

There are four basic types of behavior that characterize conduct disorder:

- Physical aggression (such as cruelty toward animals, assault or rape).

- Violating others’ rights (such as theft or vandalism).

- Lying or manipulation.

- Delinquent behaviors (such as truancy or running away from home).

Screen Addiction

Screen addiction is when a person uses technology excessively and becomes dependent on it. Screen addiction mainly involves smartphones, tablets, computers, and televisions. It is identified by a compulsive need to use these electronic devices, regardless of the negative impacts on daily activities and obligations such as work, school, or social relationships.

Screen addiction encompasses many technological addictions, including addiction to social media, video games, the internet short videos or in general just surfing. It can lead to a wide array of physical and psychological problems, including eye strain, muscle strain, sleep disturbances, anxiety, depression, and social isolation.

Screen addiction is prevalent today due to the increased level of interactivity and stimulation people get from using technology. Technological devices offer a continuous stream of notifications, updates, and entertainment options that can be difficult for people to ignore. Furthermore, these stimuli can activate the dopamine reward system in the brain, resulting in a cycle of compulsive use and addiction.

Cell phone addiction, also called problematic smartphone use, has become a growing issue, especially among younger generations. Cell phone addiction is a psychological and behavioral dependence on the chronic and compulsive use of mobile devices, such as smartphones and tablets.

It is identified as an excessive need to check and use one’s phone or other smart device, even when it interferes with daily responsibilities or creates adverse consequences.

Social Pragmatic Disorder

A. Persistent difficulties in the social use of verbal and nonverbal communication as manifested by all of the following:

1. Deficits in using communication for social purposes, such as greeting and sharing information, in a manner that is appropriate for social context.

2. Impairment in the ability to change communication to match context or the needs of the listener, such as speaking differently in a classroom than on a playground, talking differently to a child than to an adult, and avoiding use of overly formal language.

3. Difficulties following rules for conversation and storytelling, such as taking turns in conversation, rephrasing when misunderstood, and knowing how to use verbal and nonverbal signals to regulate interaction.

4. Difficulties understanding what is not explicitly stated (e.g., making inferences) and nonliteral or ambiguous meaning of language (e.g., idioms, humor, metaphors, multiple meanings that depend on the context for interpretation.)

B. The deficits result in functional limitations in effective communication, social participation, social relationships, academic achievement, or occupational performance, individually or in combination.

C. The onset of the symptoms is in the early developmental period (but deficits may not become fully manifest until social communication demands exceed limited capacities).

D. The symptoms are not attributable to another medical or neurological condition or to low abilities in the domains of word structure and grammar, and are not better explained by autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder), global developmental delay, or another mental disorder.